By Erin Henry

Interim CEO and Chief Development Officer

Reach Out and Read

Twenty-one years ago, my wife, Dora, and I stood in a long line at Cambridge City Hall, giddy and slightly stunned, holding marriage license #117. It was the day same-sex marriage became legal in Massachusetts, and a moment we weren’t sure we’d ever see in our lifetimes — a legal recognition of our love and our right to build a life together.

This year, we celebrated that anniversary with our daughter, Arden, a bright and fierce junior at Suffolk University who embodies the future we dreamed of that day. Watching her grow up with confidence in who she is, and knowing she comes from a family that is seen, valued, and protected, has been one of the greatest joys of our lives.

But the truth is, that sense of belonging isn’t guaranteed — not now and not for everyone. At a time when diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts are being rolled back and books featuring LGBTQ+ characters are under attack, it’s clearer than ever that visibility is something we still have to fight for. Especially for children. Especially in the stories that help shape how they see themselves and what they believe is possible.

Arden taught us that.

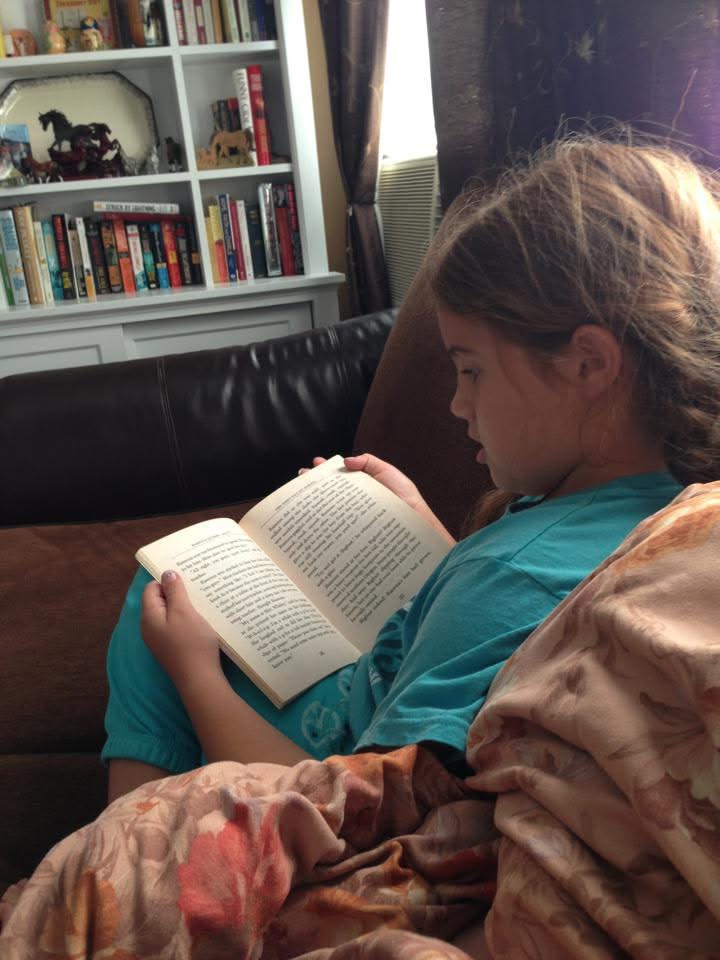

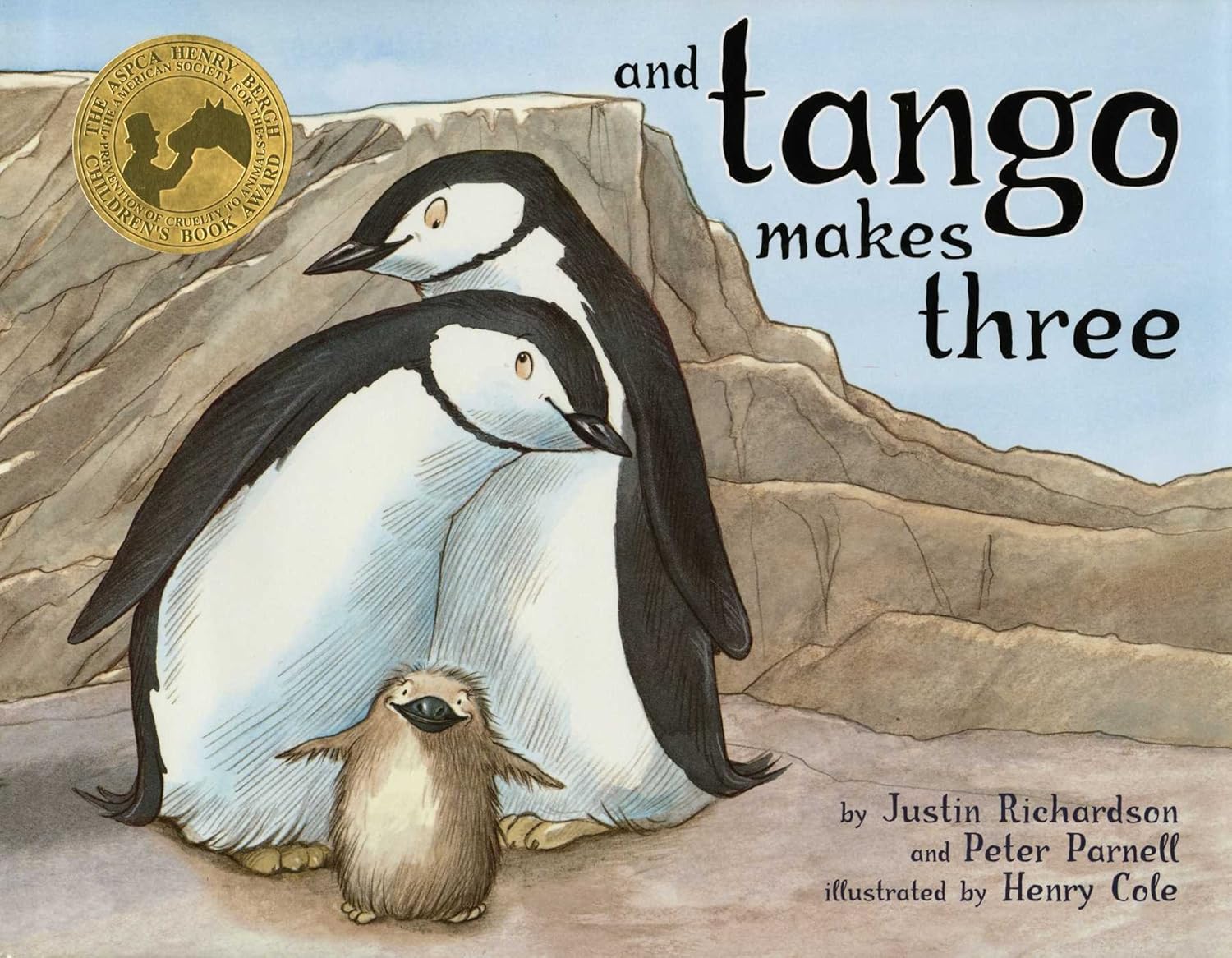

As a little girl, Arden loved to read with us. She was a sponge for stories. But books featuring two moms or families that looked like ours were few and far between, so we were drawn to books where families were just … different. “Curious George” was a perennial favorite in that lane. And the first time we read “And Tango Makes Three” — the story of two male penguins, Roy and Silo, who form a pair bond and raise a baby chick together at the Central Park Zoo? Something quiet, yet profound happened.

Though we eventually built a small collection — “Molly’s Family,” “Mom and Mum Are Getting Married,” “King and King” — “Tango” is the story that stayed with Arden most, because for the first time, she saw a family that looked like ours. Not a lesson or a controversy, just a family, wrapped in love and everyday care.

Every child deserves that.

I see in my work every day how powerful a book can be when it reaches a family at just the right moment. Sometimes it’s during a child’s first well-child visit, when a pediatrician hands a new parent a book and encourages them to read aloud. Other times it’s at a toddler visit, when a child grabs a book off the exam table and crawls into a caregiver’s lap to flip through the pages. These small moments matter because they’re how children begin to understand language, love, and belonging.

And the stories they see in those books? They matter just as much.

When kids are surrounded by stories that include all kinds of families — including families with two dads, two moms, single parents, grandparents as parents, families of multiple races, and families by choice — they grow up knowing that love isn’t one-size-fits-all. It isn’t a mold to fit into. It’s something to build, shape, and share.

But when that representation is missing or, worse, is deliberately erased, children begin to wonder if there’s something wrong with the way they live or love. A book may seem like a small thing, but to a child who feels different, it can mean everything. A mirror. A lifeline. A quiet reassurance that they’re not alone.

Though progress has been made since Arden was little, particularly through access to bookstores online, inclusive, culturally responsive books remain hard to find. The result isn’t just a loss of stories — it’s a loss of connection. And children notice. They’re paying attention, even when we think they’re not.

When a story is missing a family like their own, a child can go missing. They stop seeing themselves as worthy of being part of the narrative. They start to believe that their family doesn’t count, or that their story shouldn’t be told.

Arden has grown into a young woman who doesn’t just advocate for herself or kids with two moms or two dads. She sees the bigger picture. She sees the value of books as “windows,” stories that can help children see beyond themselves and build empathy and respect for other families and cultures. The impact of those windows and mirrors — books that reflect their own lives back to them— can shape how children see the world and how they see their place in it.

This Pride Month, I’m not just reflecting on the milestones Dora and I have reached or the progress we’ve witnessed. I’m thinking about the next generation and what they need from us now. They need books that reflect the world as it is and the possibilities of what it can be. They need to know that they are loved, protected, and seen. A good book at the right time can do just that. It can heal. It can strengthen. It can open a door to a bigger, kinder world. As a mom, I’ve watched that happen with Arden. And in my work, I’ve seen it happen in doctor’s offices and exam rooms across the country.

We need more of those stories. We need books that say, “You matter.” Books that whisper, “You’re not alone.” Books that show kids not just who they might become, but who they already are.

This month, Dora and I will celebrate our marriage as we always do: with gratitude, laughter, and probably a few happy tears. But more than that, we’ll celebrate the hope we’ve tried to give Arden and the hope she now carries forward into the world.

Because when our daughter finds her place in the story, she doesn’t just grow stronger. She helps write a better one for everyone.

About Erin Henry

Erin Henry is a transformational nonprofit leader with 25+ years of experience driving organizational growth, philanthropic strategy, and mission impact across the health care and nonprofit sectors. She currently serves as Interim Chief Executive Officer for Reach Out and Read, a national nonprofit that promotes children and families by equipping caregivers with guidance and books to make reading with their young children a meaningful part of daily life.

As Chief Development Officer, she’s led Reach Out and Read’s network in historic fundraising and worked with leadership to plan the next era of the evidence-based program, which serves 4.6 million children a year. Erin spent much of her career as a fundraiser for academic medicine, working primarily in corporate and foundation relations, strategic partnerships, and events. She is a former member of the Board of Governors for the Human Rights Campaign.

Erin, her wife Dora, and their daughter, Arden, live on a horse farm in Atkinson, N.H.