July 2025

By Dr. Robert Needlman

When COVID hit, I gave up my primary care clinic to devote full time to developmental behavioral peds. I see things differently now that I don’t have lots of healthy babies to play with. For example, I think more about dyslexia.

Reach Out and Read started with the idea that the problem was a lack of exposure to reading aloud, not that dyslexia was making things difficult for either the parent or the child. But a parent’s reluctance to read aloud may start with early unhappy reading experiences (i.e., dyslexia). How do we help parents convey a love of books that they don’t actually feel?

While we counsel parents to “tell the story, don’t read the words,” this advice may not go deeply enough. The message that “reading aloud is important” may only add to a dyslexic parent’s sense of inadequacy and anxiety. Dyslexia is often a well-guarded secret.

So, what do we do? When we approach the topic with curiosity and a willingness to support parents’ aspirations, even if, and especially if, they have barriers to overcome, we give parents permission to lower their defenses and explore doing things in new ways.

In my DBPeds practice, I often diagnose dyslexia in my patients (and their parents!). And of course, I always recommend reading aloud as a way to build vocabulary and comprehension and keep a love of books alive. Sometimes my patients and I even get to do a little interactive reading aloud. Parents can see how much fun we’re having, and they get the idea that they can do it, too. Reading aloud can be joyful and powerful at any age!

The Power of YES

April 2025

By Dr. Leora Mogilner Associate Professor of Pediatrics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

In a pediatrician’s world of no’s — no cereal in the bottle, no sleeping on your belly, no honey, and on and on — Reach Out and Read has given me the opportunity to be Dr. Yes!

Yes — you can read with your baby, any time, in any language, and you can be as serious or as silly as you would like to be. Yes — you can read the same book over and over with your toddler if that is what makes them happy.

I found myself spending so much time telling parents what they could not do with their babies that I decided to use the book as a gateway to all the wonderful things parents could do.

“The baby already recognizes your voice and your smell and loves being held by you while you read or sing to him.”

“When you are exhausted, the book will give you new material to talk with her about.”

By using the book to observe how the parent and child interact, I can offer positive feedback and encouragement about what I see. For parents who are feeling exhausted and drained (and what parent of an infant does not feel exhausted?), being able to provide support and advice is a wonderful thing for me as a pediatrician. I use book sharing and storytelling as a scaffold for familiar routines parents should weave into their day — like naptime and bedtime. Once the power of the book has been unleashed, there is no going back. Parents love to share anecdotes about their children’s favorite books, and when children are older, they tell me themselves about their favorite characters and subjects. And the joy on parents’ faces when I bring in a book in the native language — be it Spanish or Bengali or Chinese — is very special. I am so grateful to Reach Out and Read for helping me unleash the power of Yes!

January 2025

By Dr. Imani Sanders in Broward County, Florida

As I handed the PHQ9 (Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression/Anxiety) survey to the teenager, I noticed his face frown and eyebrows furrow. He slowly placed the survey on the nearby seat and gazed at the ground. This was my first visit with this patient, and I came to find out that this was his first visit with a physician since he was a toddler.

Uniquely situated in a bustling diverse city, this clinic often provided care to children who had just immigrated from other countries. It was not uncommon to encounter toddlers and school-aged children who had not seen a doctor recently, but this was my first encounter with a 16-year-old in this situation. This teenager was tall and poised, yet you could see the shyness in his eyes. He responded to my questions consistently — yet often gave one- to two-word answers and looked to his mom to fill in the gaps. In gathering more history, I learned that he could not read.

His mother went on to describe learning challenges in his home country that were noted around school age, but she also talked about the inability to get him resources that would have helped with appropriate cognitive stimulation and growth in his reading skills. This situation was layered, challenging, and complex. (I’m happy to report that he is now enrolled in our state’s Diagnostic Learning Resources System, getting evaluated to identify any specific learning disabilities, and is in the process of enrolling in a specialized trade high school.) While this may seem like a story of extreme circumstances, to me, it underscored the importance of the intersection of pediatric medical care and youth literacy. It also emphasized how learning challenges can be disguised as initial perceptions of sadness and anxiety.

Reach Out and Read has transformed how we as pediatricians guide families in promoting developmentally appropriate literacy. It is more than giving a free book to a family as a reward for complying with the recommended visit schedule and more than a peace offering to a child who is still distressed by that otoscopic exam … It is a springboard for enlightening conversations with parents where we discuss language milestones and educate them on the importance of daily reading and math skills.

I think about that teenager when I encounter our infant and toddler patients. While he is making strides now, how would his life be different if there had been earlier and better access to literature resources where he grew up? As we provide exciting age-appropriate books and encourage parents to dedicate that special daily reading time, we are playing an integral part in helping them optimize the trajectory of their children’s neurological development and centering books as a tool for advancing cognitive and academic skills.

October 2024

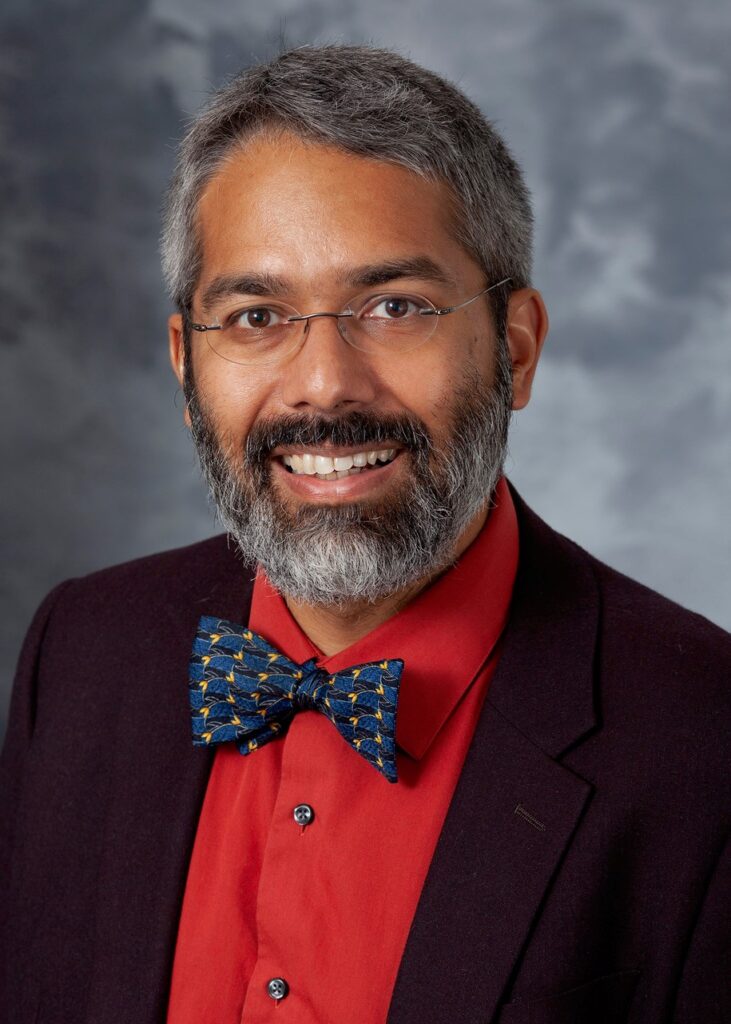

By Dr. Dipesh Navsaria

I frequently think about Reach Out and Read when working with our physician assistant students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. As Medical Director of the program, I help with their history and physical exam practical sessions and have the opportunity to watch them make their way through their first attempts at patient interviews and exams. While these students won’t formally hear about Reach Out and Read until a couple of semesters later, it still is foremost in my thoughts.

Why? Because at this critical, formative moment in their training — where the ideals of careful listening, skillful observation, and thoughtful engagement have not yet run up against the challenges of packed schedules and documentation pressures — I always think about how we can both let them grow into a comfortable, eventually expert way of engaging with whom they serve, while also not becoming complacent and efficient to a fault where large parts of the patient’s story are missed.

I think Reach Out and Read honors both that “beginner’s mind” — it’s a scaffold for how to engage with families in well-child visits — but also holding the “expert mind” accountable amidst the realities of contemporary medicine. Our focus on relational health centers the family in our engagement and assists us with supporting those everyday interactions that make such differences in the socio-emotional development of their children.

So whether you’re new to clinical practice or an experienced veteran, whether you directly work with trainees or not, Reach Out and Read is, I think, clinically centering in important ways. The next well visit you walk into, take a moment before opening the door and reflect for a second on this, and see how it supports you doing the great job you do. And if you have a learner with you, share that reflection with them out loud — it’ll make a big difference to their development as well.

The Power of the Book

July 2024

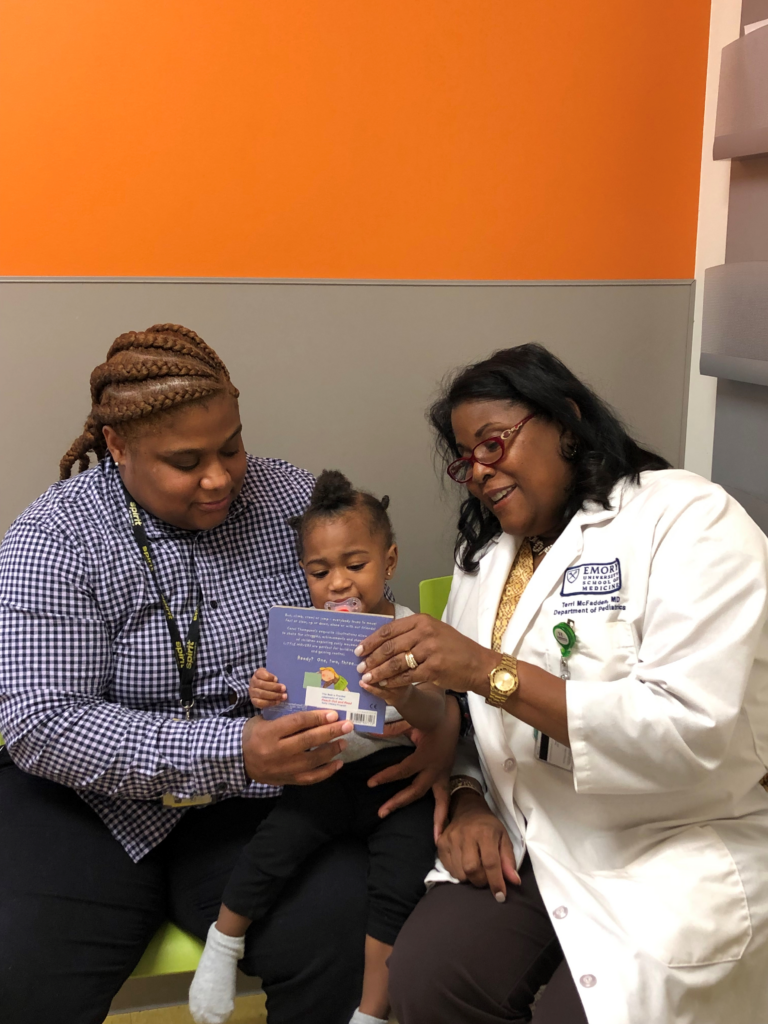

By Dr. Terri McFadden

It was a typical afternoon in my Thursday resident continuity clinic. As I glanced up at our clinic patient tracking board, I realized that our residents would be quite busy! Indeed, they were busily making their way through the session, seeing patients as thoroughly and efficiently as possible.

As my resident discussed his next patient, an 18-month-old girl, I thought about my questions for him. Was her growth on track? Did she appear developmentally appropriate? And then obviously, “What was your interaction with her around the book that you gave?” This was an excellent resident, as they usually are. He looked at me and said, “I am so sorry, but I forgot the book.” This happens sometimes, so I directed him to go back into the room with the book and to engage the patient and mom using the book as a tool. “I’ll go with you and listen quietly.”

As we entered the room, the toddler was walking around screaming at the top of her lungs, while her young mother sat quietly looking at her phone. I thought to myself, “Oh boy. This may not go well.” But in an instant, the resident kneeled in front of the toddler and began to point out items in the colorful book that he had selected for her. She immediately stopped crying and began to point to the characters found on the page. Slowly, the mother looked up from her phone and began to watch the interaction between the resident and her daughter.

At this point, I decided to chime in, so I said to the mother, who was dressed in a work uniform and looked tired, “It seems as if Kayla really likes books!” The mother looked at me and said, “I guess so.” And our conversation began.

Eventually, we discussed the challenges that she faced as a young mother who worked as much as possible to provide for her family. In the end, she thanked us for the book and for the tips we provided for using it with her daughter. While a single book cannot address every one of the many issues that our families often face, in that moment, I was reminded of the power of the book in the hands of a caring clinician.

April 2024

By Dr. Perri Klass

There were at least four screens in the exam room with the toddler. There was the desktop computer, of course, with the EPIC chart open, and there was the monitor with the interpreter, and there was the phone in the hand of the toddler’s adolescent sister, who was busy texting, and there was the phone in the resident’s hand because he was looking up a medication that the mother had just handed over, something they had brought with them from another country, and trying to figure out what it was.

None of these were “bad” screens, or screens being used in “bad” ways. Everyone was using them appropriately, from the adolescent sibling who was quietly communicating with friends while obligingly spending the afternoon at a toddler’s primary care visit, to the resident, who was entering information into the electronic health record while double checking an unknown medication on the web. But in order to figure out why his patient might have taken that medication, he had to look to the monitor with the interpreter, ask the question that was translated for the mother who then took out her own cell phone and sent a text message, seeking more information from another family member.